Reality Fiction

Thrilling Wonder Stories is the modest title of an annual event (now it its third year), this year hosted by Liam Young (Tomorrow's Thoughts Today) and Matt Jones (BERG London) at the Architectural Association in London. I attended the event on Friday and left brimming with new ideas, full of a renewed sense of idealism about what is possible in film, art and storytelling.

The future may not be what it used to be but, maybe, just maybe, great cities of yore – London and New York – still have a special part to play in a 21st century society defined by a globally networked capitalism that is dissolving physical space and making location increasingly irrelevant. There may be no maps for these territories but, as we strive to find our way through this shadowy new topography – a transparent 3D chess board extending to infinity – the intersection where storytelling and technology meet is likely to provide an invaluable light in the dark. The story, which has shaped understanding for thousands of years and is arguably the ultimate human technology, still has the power to remake the world, offering opportunities for transformation, renewal and a sense of genuine, Vaclav Havel inspired, hope.

Part One – Worlds of Wonder: Far From Home

The first speaker in this celebration of storytelling and technology was Christian Lorenz Scheurer, a Swiss concept artist who has lent his talents to everything from Hollywood movies, animations, comics, paintings, video games and theme parks, as well as some very elaborate, very secret building projects in Beijing, Moscow and Dubai. He described his creative process as an attempt to investigate The Anthropology of the Imaginary – asking questions about the sorts of people who live in the world he is trying to imagine and using that information as his guide. He said that he liked working on movies and video games in particular because they allow him to be like Gustav Klimt, designing architecture, creatures and fashion.

Having recounted his early years in Hollywood, calling up major studios and asking to speak to Tim Burton and Steven Spielberg, he talked about his work on a succession of successful failures and failed successes, including Fifth Element, Titanic, What Dreams May Come, Dark City, The Matrix and The Day After Tomorrow. Then he got bored with Hollywood, he told us, and went to work in Japan on Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, which was a five year project and a massive commercial flop, but also a Petri-dish for other's successes – without that project, no Gollum, no Avatar, he said.

In Hollywood, of course, the right image (and all of his art was absolutely beautiful) is worth a lot of money, not to discredit George Lucas in any way, Lorenz Scheurer told us, but it was probably the dozen or so Ralph McQuarrie sketches and paintings that got Star Wars its green light, as opposed to Lucas' 20 scribbled pages of story outline. He also described working on a painting of the Sentinel robots for The Animatrix, which the Wachowskis described as looking like a ball with 'eels of made out of quicksilver' moving around it, burrowing into the earth – a thrilling reminder of just how powerful words can be in the right hands.

Then the conversation was joined by a representative from SPOV, an agency that works on CGI animation sequences for TV programmes, games and movies; and Gavin Rothery, who worked as concept artist on Moon, directed by Duncan Jones. Rothery gave some interesting insights into the processes involved in working with old fashioned models which, in combination with a bit of CGI magic, can still be transformed from a children's toy pulled by a piece of string into a credible lunar rover on the surface of the moon. There is a good reason why film's like 2001: A Space Odyssey, the original Star Wars, Alien and Blade Runner still stand up to this day.

This led onto a conversation about the difference between good science fiction and bad science fiction. Good science fiction is almost invariably the kind that creates some rules and then sticks to them; it is when those rules are broken that an audience looses its ability to suspend disbelief – an ethos that is as true of the narrative as it is of the design. In the original Star Wars films, Liam Young reminded us, none of the vehicles have wheels, whereas on the prequels there are wheels and, as a result it doesn't look like Star Wars. It is that extra three or four percent attention to detail that makes all the difference when you are asking an audience to invest their emotions in something fantastic.

All three contributors agreed that one of the best things that any designer or storyteller can do when they have the freedom to create almost anything is to put some limits on it. This principle was well illustrated (ha!) in another set of pictures Lorenz Scheurer showed us from his first film project, an unmade Belgian science fiction movie called Rax wherein the director set three criterion for his fantasy world; no nuts, no bolts, everything has to be steam powered and everything has to be made out of ceramics.

In storytelling in general, but in science fiction in particular, so much inspiration comes from playing the childlike game of, 'What if?' What if Gaudi was not run over by a tram but had carried on building the Barcelona he envisioned in his head? Might it have looked something like this?

A welcome reminder of the vast amount of honest effort and endeavour that goes into creating movies, regardless of the final outcome – something that is well worth keeping in mind when assessing the final product. You can rest assured, almost every detail you notice and many that you don’t has been thought about and sweated over by talented artists and technicians whose sincere intention is to make something that enables people to suspend their disbelief and become emotionally involved in the reality of the fiction.

Behind the Scenes – Blood, Guts and Hydraulic Fluid

Andy Lockley, visual effects artist at Double Negative (he was keen to stress the difference between special effects and VFX, which are frequently confused, he said), who has worked on such films as Captain America, The Dark Knight, Inception (for which he won an Oscar) and upcoming The Dark Knight Rises, was the first person to speak on the second panel and for copyright reasons all of the live feeds were turned off and recording of any kind prohibited. ‘Don’t even remember’ he said. For that reason I am not sure how much I am allowed to say about his contribution, but, I think I am on safe ground saying that he spoke about the different approaches taken by some of the different directors he has worked with and was particularly enlightening about his working relationship with Christopher Nolan on Inception and the Batman films. Apparently, Christopher Nolan's approach to special effects and the fantastic is always tempered by what he calls, 'our disappointing reality'. Every explosion, every effect, every car chase in a Christopher Nolan film has to have that slight sense of 'disappointment' because that is his experience of reality, a useful safety lever that prevents his films from veering too far into the realm of the impossible, one suspects. Lockley's advice to aspiring artists, designers and creators was 'don't think you know better than reality, always copy things, always have reference and make things dirty'.

The next person to speak was Gustav Hoegen, an electronics engineer specialising in animatronics work on films, who has lent his expertise to such diverse projects as Clash of the Titans (2010), The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy (2005) and, perhaps most intriguingly, the new Alien prequel Prometheus. He demonstrated how he turns biomechanics into mechanics, imitating life through engineering and, while conceding that he is never going to be able to compete with computer special effects – 'I am quite intimidated by it to be honest', he said – he did a great job of explaining how his practical effects differ; being present on the set, improvising, thinking on your feat, no time to plan, ‘hand shaking as you try to wire something in’ – animatronics is very much an old-fashioned discipline.

But not quite as old-fashioned as what followed.

Taxidermy!

Not the Victorian kind with specialist chemicals, preserving agents and delicate dis-and-re-assembly, no, a live, do-it-yourself taxidermy demonstration by a wonderfully bonkers woman called Charlie Tuesday Gates, who told us that she found most of her specimens by the side of the road and has nothing but scorn for vegetarians (being a vegan herself). She proceeded to skin a dead rabbit – a lot like ‘peeling an orange’, apparently – a sight I definitely did not expect to see when I woke up that day. While she did so she regaled us with the kind of barmy anecdotes one might expect from a woman brassy enough to start doing taxidermy as a hobby and then end up making a career out of it – a welcome intrusion of ever-so-quirky in-your-face humanity.

Following that madness, Vincenzo Natali’s disembodied head joined us, speaking live via Skype from his home in Toronto. He spoke about his predilection towards science fiction, the life-changing experience of watching Star Wars aged eight and his ambitious plans for new movies based of JG Ballard's High-Rise and William Gibson's Neuromancer. He expressed his view that Ballard's books were more akin to surrealist paintings than traditional novels and also dropped some fascinating insights about his approach to adapting Neuromancer. He said, in its simplest form, he sees it as a heist movie which gets a bit more complicated in the final third, and, given that Neuromancer is 'almost not science fiction anymore', he plans to shoot most of the movie on location, adding a few augmentations in post production. The real challenge of course will be realising cyberspace, but, unsurprisingly, he wasn’t giving anything away with respect to that.

Part Three – Strange But True: When Robots Rule the World

This third panel started with a swarm robotics demonstration in which two dozen or so small, cylindrical bots with sensors on the outside and embedded micro-controllers and motors on the inside gradually manoeuvred themselves into a pattern as determined by a light source. It was a modest demonstration of a very powerful programming methodology to do with designing redundant systems (not all of the robots can succeed), which prioritises the aims of the many over those of the one.

Dr Roderich Gross from the Head of the Natural Robotics Lab at the University of Sheffield continued the robot theme with his presentation about some of the more sophisticated swarm robotic systems currently under development in the laboratory; before Philip Beesley, an experimental architect, joined the conversation to give a very detailed, intellectually engaging talk that I am sure will have thrilled and enthused any architects present. I enjoyed it but cannot pretend to have understood it in its entirety. The concepts he was describing and even his way of talking about them was very much a new world for me. What he seemed to be proposing was a more interactive and socially engaged design methodology, which might act as a counterpoint to the essentially alienating approaches promoted by thoughts about Euclidean geometry and Platonic solids. Fascinating stuff somewhere between architecture and installation art, including references to material properties and structural mechanics, alongside allusions to 17th century paintings, theology and philosophy. A very pure design aesthetic and ethical framework intended (I assume) to provoke thoughts about how sensors and interactive elements might be incorporated into the built environment by looking at the problem from an alternative perspective, outside the typical run of the mill.

This talk ended on a fascinating note, with the contributors being questioned about the ethics of their research, Beesley expressing his concern about the very fine line between an interactive architectural element imbued with threat and one that is soothing and encourages calm.

The Heart of the Matter

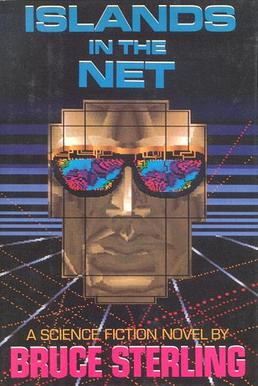

The last panel was comprised of Julian Bleecker, who wanted to tell us why just because something is not sold in Walmart, it does not mean it is not real; Kevin Slavin, who spoke about how algorithms are taking over Wall Street, motivating people to level mountains and terraform the Earth itself in order to install faster fibre-optic lines; and Bruce Sterling, who disarmed everyone by telling us that the only things that really provoke wonder are things in nature such as the size of the universe and the age of the earth, before exhilarating everyone with a story about the most thrilling and wondrous sausage he could imagine – specifically, a radioactive Chernobyl Przewalski horse sausage shot by a bunch of bored Ukrainian teenagers, rendered by a DIY butcher and eaten by one Steve Jobs on a business trip to Moscow – a Gothic High-Tech story that chimes with the fevered times in which we are living.

That was the precis for the epic conversation that followed. Unfortunately, I had to leave early and did not catch it in its entirety, but what follows are some of the provocations I might have contributed if I had the balls and the microphone.

Despite its success, and it was a big success, at the centre of the event was a contradiction that was never directly addressed in a wholly satisfactory manner. Namely, the perennial struggle between art and commerce. Maybe the problem is intractable but it is impossible to ignore the fact that it is Hollywood and big business that fund fantastic concept artists to create visions of other worlds; it the military-industrial complex that empowers scientists to undertake swarm robotics and advanced artificial intelligence research; and it is the voracious demands of the market that are incentivising physicists and mathematicians in New York and London to develop ever more advanced derivative trading products and algorithms which, once they are unleashed, nobody understands.

So, on the one hand, it is global capital that makes these thrilling wonder stories possible, but, might the efforts of the very brilliant people who create the art, engineer the robots and programme the algorithms be better directed? In spite of the massive amount of money, effort and man-hours that go into designing and developing Hollywood films, the finished product is rarely as evocative as the concepts that precede it – as Lorenz Scheurer conceded, Hollywood producers invariably demand that whatever fantastic science fictional city he has created become New York. As mentioned by Liam Young, the most advanced robots in the world are invariably produced for the military, which uses them to destroy – we know that drone attacks are already alarmingly commonplace in Pakistan. And, as Kevin Slavin told us in his talk, the algorithms, which are already responsible for 70 percent of trades in the US, are already making their way into executive roles, abstracting information and replacing human agency, producing 'information without an author'.

There was a brief refutation of the idea that a concept only becomes real when it can be productised or marketed. Julian Bleecker proposed that concepts themselves, as realised in paintings, films, animations or good ol' fashioned words on a page, are real because they fires our imagination and make us think about what could be – a thrilling defence of authors and artists that needs to be made even more vigorously, I think. He said that every time we apologise for presenting something that is not 'real', we are submitting to a capitalist ideology that is just plain wrong. In order to illustrate his point, Bleecker, who wrote his PhD (signed by former governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger, no less) about the social and cultural power of the 'special effect', told us a story. It was a true story about how Samsung's lawyers used the poster for the film 2001: A space Odyssey, which depicts an astronaut standing on the surface of the moon holding what appears to be a wireless touch screen information device, to defend a copyright lawsuit brought by Apple. The lawyers argued, with a straight face, that the idea for the product was in existence prior to Apple's patent and therefore, Samsung had not breached intellectual property law; in effect, Apple had stolen the idea from Stanley Kubrick and his collaborators in the first place! This is ironic for a number of reasons but most especially because the same corporations that prompt us to think of artistic and design endeavour as 'not real' in the first place are the first to assert just how real these things are when it suits their interests. My question therefore is, what is the alternative? How do we create a society in which art is valued as much as product? Does the change have to come from individuals asserting their own standards or does there need to be some sort of institutional change? Is such a change possible and, looked at from a broader perspective, is it necessarily preferable?

The second questioner wanted to know the panellists thoughts about how one might express the very complicated ideas under discussion to a child. He drew upon Kevin Slavin's previous comments – if chess is an analogy for war and Monopoly a crude metaphor for capitalism, Code War (a 1984 computer game in which the players duel with algorithms) is not metaphor or analogy at all; it is real, being played out on the world's stockmarkets and elsewhere – saying that, despite their sophistication, he could still teach chess and Monopoly to an eight year old, but, he could not do the same with Code War. What tools might one use to introduce a child to the ever-changing world in which we live? Slavin said that computer games are a pretty good start, drawing our attention to their sophistication by making the comparison that all he had to play with when he was a kid were six dice and 52 cards. The question, I didn't get the chance to ask is, what games? There were a lot of people keen to give their props to computer games throughout the event and, much as I can understand why, if we are honest, computer games are not nearly as good as they ought to be. In fact, computer games are a good example of an industry that has been coarsened by an industrial-marketing machine that requires a certain type of game. In the early years of home computing, games were quirky and idiosyncratic – Lucasarts adventure games, Microprose strategy games, Codemasters sports games – designed to appeal to a small number of discerning consumers. Now that computer games are big business they have been homogenised beyond all recognition, boxed off into just a few categories. World of Warcraft, Call of Duty, Halo, and a few other Blockbuster titles dominate the market. 60 percent of games produced are first-person shooters of one kind or another. Where are the rich new worlds of creative possibility we are all being promised? When you think that there are more possible moves in a single game of chess than there are grains on the entire planet – there is some thrilling wonder for you! – Call of Duty, in spite of all of its aesthetic sophistication, starts to look a little bit weak, a bit tame. The graphics (which are beautifully rendered by very skilful people I'm sure) have improved exponentially, but the actual game mechanics have not advanced far beyond Space Invaders – pointing a target at a screen in order to shoot and kill things. I agree that computer games have enormous potential, maybe even more than modern day movies, but they are not there yet.

Unfortunately, it was at this point that I had to leave – I very much wanted to hear from the sound effects and music panel that was going to follow. I would also have very much liked to have asked the panel, if cynicism is the wrong response because it leads to inaction (and I would agree with that 100 percent by the way), what is the right response? What do we need to do to motivate ourselves and others to take effective action? Because surely the status quo, moulded by powerful interests beyond our control – supernational corporations, unaccountable media moguls, oligarchs and even algorithms which 'decide' what information we see and what information we don't – has to change. The Occupy protesters might be incoherent and hypocritical, but their demonstrations stem from legitimate concerns and frustrations about perceived inequalities and cronyism. Where are our jobs going to come from? Where are the opportunities for those with talent to rise to the top, based on ability as opposed to money or class? The forces of global capitalism seem to be fighting against us, and bankers, politicians and journalists at the top of society do not seem to be being held to account.

In brief, the event left me buzzing with ideas, questions left unanswered. In a world in which creators and innovators have seemingly been pushed to the margins in favour of a market friendly corporate blandness, it was great to see something that wanted to celebrate the imagination, the power of dreams and the magic of storytelling. The next part is probably my job.

Subscribe to my feed

Subscribe to my feed